The "Compromise" of Caspe

[204] Six claimants to the throne. Electors choose Ferdinand of Castile. He secures the crown. Attempts to end the Great Schism. Quarrels concerning finance. Premature death of Ferdinand.

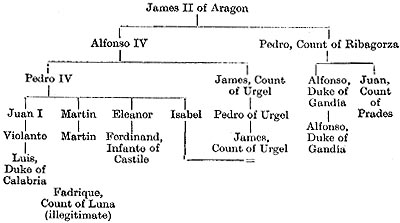

On the death of King Martin there was no direct heir to the throne, and six claimants came forward. The first was James, the Count of Urgel, who based his claim upon his own rights and those of his wife, Isabel. He was the great-grandson of Alfonso IV, and his wife was the daughter of Pedro IV by his fourth wife, Sibila. Secondly, there was Alfonso, the Duke of Gandía. He was the son of Pedro, the Count of Ribagorza, and therefore grandson of James II. He died in the course of the discussions on the succession, and his son, also named Alfonso, took his place. The third claimant was Luis, Duke of Calabria, the son of Violante of Anjou, the daughter of King Juan. Fourthly was Ferdinand, the Infante of Castile, the son of Eleanor, who had married Juan of Castile, and was therefore the grandson of Pedro IV. The fifth claimant was Fadrique, the Count of Luna, an illegitimate son of the Infante Martin. Lastly, there was Juan, the Count of Prades, the brother of the first Alfonso, who was Duke of Gandía, and who came forward, upon the death of the Duke, considering that his rights were better than those of his nephew.(1) It was to be expected that with a vacant throne and so many claimants disturbances would break out, and the Catalans entrusted the government to twelve commissioners who succeeded in maintaining order, but Aragon was disturbed by the family quarrels of the Luna and Urrea parties, which were further exasperated by the attempt of James, the Count of Urgel, to secure recognition as Governor General of the kingdom. In Valencia things were [205] even worse. The claims of the Count were there espoused by the party led by the family of Vilaregut, who were opposed by the Centellas. Sardinia now seized the opportunity to try to secure independence, while Sicily was divided between the causes of Queen Blanca, the widow of the Infante Martin, and the supporters of Bernardo de Cabrera. It soon became obvious that only two candidates need be seriously considered. James, the Count of Urgel, was a handsome and attractive young man, whose personal charm and liberality in gifts and promises had secured him a large body of supporters. He could rely upon the support of Catalonia almost as a whole and of many localities in the other two kingdoms. He seriously damaged his prospects by his attempt to seize the position of Governor General, which was usually held by the immediate heir to the throne, and aroused so much discontent in Aragon and in Zaragoza that he actually improved the chance of his chief rival Ferdinand. Ferdinand was the son of Leonor, the daughter of Pedro IV, who had married Juan, the son of the Count of Trastamara. His elder brother, Henry III, became King of Castile, and, on his death in 1406, left an heir named Juan, barely two years of age, whom he recommended on his death-bed to his brother's care. Ferdinand undertook the responsibility, and performed it honourably. He refused to listen to any suggestions that he might himself occupy the throne, and secured the coronation of Juan II under the regency of himself and the widowed Queen. Apart from domestic disturbances in Castile, the [206] country was also involved in a dangerous struggle with the Moors of Granada. Ferdinand successfully dealt with these difficulties, and his defeat of the Moors and the capture of their chief fortress gave him the title "El de Antequera." While he thus restrained any ambitions he may have had to rule Castile, on the death of his uncle he had no hesitation in claiming the crown of Aragon, though there were not wanting critics who pointed out that Juan II of Castile had a better right to the crown, as being in a more direct line of descent. Ferdinand was strongly supported in Aragon, as he made no aggressive claims and professed to rely upon justice and right, and in sending ambassadors to Aragon to advance his claim he was careful not to cross the frontier in person. Of the two contending parties in Aragon, that led by Antonio de Luna declared for the Count of Urgel, but the party of Urrea which supported Ferdinand also secured the co-operation of the Archbishop of Zaragoza, and his influence brought over most of the influential men in the kingdom to the side of Ferdinand. Two opposed policies were thus represented: the party of the Count of Urgel stood for separatism, while the supporters of Ferdinand looked for a movement towards peninsular union with the help and friendship of Castile.

The Count of Urgel then proceeded to ruin his prospects by murdering the Archbishop, in the hope of breaking up the opposition party. The Archbishop was attacked and killed on a journey by the adherents of Antonio de Luna, but their attempt to seize Zaragoza was frustrated in time, and the general horror aroused by this treachery contributed to strengthen the cause of Ferdinand. Thus it was possible to gather an assembly representative of Aragon in September 1411, at Alcańiz, while the Catalan representatives had previously assembled in Tortosa. It was more difficult to secure any agreement in Valencia. The famous churchman and orator, Vicente Ferrer, whose influence in Valencia was considerable, espoused the cause of Ferdinand, and, after the contending parties had fought a battle at Murviedro in January 1412, in which the Count's party was utterly defeated, some measure of agreement was secured. Pope Benedict was indefatigable in his attempts to bring the representatives of the three kingdoms together, and, after lengthy negotiations, it was decided that each kingdom [207] should nominate three persons who were to meet and decide upon the respective claims now before the country. The claimants were allowed to be represented by their proctors or lawyers to make out their case, and every precaution was taken to preserve the commission from outside interference. The Aragonese representatives were Domingo Ram, the Bishop of Huesca, Francisco de Aranda, a Carthusian monk, and Berenguer de Bardají, one of the most distinguished lawyers of his time. Catalonia was represented by Pedro Zagarriga, the Archbishop of Tarragona, Guillermo de Vallseca, a lawyer of high repute, and Bernardo de Gualbes, learned both in canon and civil law. The Valencian representatives were Bonifacio Ferrer, the head of the Carthusian Order, the Dominican, Vicente Ferrer, who enjoyed a wide reputation even beyond Spain for piety and eloquence, and Ginés Rabasa, a lawyer. These nine electors met in Caspe, situated on the Ebro and belonging to the Knights of St. John. After deliberating for thirty days and hearing evidence, on June 28, 1412, they announced that they had decided in favour of Ferdinand of Castile as the nearest relative of the deceased King, an announcement made by Vincente Ferrer as the climax of a long and eloquent sermon. It was not to be expected that any choice would produce universal satisfaction, and chroniclers vary considerably in their accounts of the feeling with which the announcement was received. But it became plain that the three kingdoms as a whole were prepared to support Ferdinand, and it was to be hoped that the Count of Urgel would accept the decision of the commission.

Ferdinand I, therefore, made his way to Zaragoza, where he agreed to observe the liberties of the kingdom. He had previously visited Catalonia and received the homage of Valencia. The election had a good effect upon outlying portions of the Aragonese dominions. In Sicily, for instance, Ferdinand confirmed the position of Queen Blanca as regent of the island with a council of advisers to help her. Bernardo de Cabrera, who had been persecuting the Queen with offers of marriage and opposition to her government, was arrested and brought to Barcelona. In Sardinia, the Viscount of Narbonne had attempted, in conjunction with the Genoese, to conquer the whole of the island, and had already secured [208] a considerable part of it, when the announcement of Ferdinand's election made him realize that he would be opposed not merely by Aragon but that Ferdinand could also rely upon support from Castile. He and his allies immediately sent an embassy to Aragon, and concluded a five years' truce. In the Balearic Islands Ferdinand had been previously recognized, and his supremacy over the Aragonese dominions thus appeared to be undisputed.

It was, however, impossible to satisfy the disappointed ambitions of the Count of Urgel. Ferdinand had excused his absence from the Cortes, had given him an honourable place at court and had promised large sums of money towards the payment of his debts, but the continual complaints of his mother and the incitement of his friend, Antonio de Luna, induced him to make plans for the overthrow of Ferdinand. He opened communications with the Duke of Clarence, son of Henry IV of England, who was at Bordeaux, and, on gaining promises of help from him and from other French nobles, he collected an army and invaded Aragon in the spring of 1413. Antonio de Luna ravaged the neighbourhood of Jaca, while the Count himself operated in the neighbourhood of Lérida, in the hope of winning support in Catalonia. The Duke of Clarence, however, was hurriedly recalled to England by the death of his father, and the help that he had promised was not forthcoming, while other nobles began to consider the imprudence of attacking so powerful an adversary as the King of Aragon. Ferdinand had already taken adequate measures for the security of the country. He had garrisoned the vulnerable spots, and when the Count's intentions became plain he collected a force from the nobles of the realm, which was strengthened by a body of Castilian knights who were supporting him in Zaragoza. The Count and Luna were besieged in Balaguer and held out for more than two months, vainly hoping that English reinforcements would relieve them, while Ferdinand's forces battered the town with every type of artillery then known. Eventually the rebels were forced to surrender, and threw themselves upon the King's mercy. In November 1413 Ferdinand commuted the death penalty which the Count had incurred as a traitor to the kingdom to one of imprisonment for life with the confiscation of his property. The King then returned to [209] Zaragoza, his position now being secure, for the coronation ceremonies which were carried out with unexampled splendour in February 1414.

Two matters occupied the King's attention immediately after his coronation. The first of these was the question of the papacy. The Council of Pisa held in 1409 had in vain attempted to heal the breach in the unity of the Church caused by the Great Schism. The Council had declared the deposition of the existing Popes, Benedict XIII and Gregory XII, and had elected Alexander V in their place; but this solution was by no means generally accepted. The Emperor Sigismund had summoned a General Council to deal with this pressing problem. As early as October 1413 he had invited representatives of all Christendom to meet at Constance in November of 1414 for a general Church Council, and invitations were issued to King Ferdinand and to Pope Benedict XIII, who had been active in Aragon, as we have seen, in conducting negotiations for the election to the throne. It was obviously necessary for Ferdinand to decide whether he should support the Spanish Pope or not. For that reason, a meeting between himself and Benedict was arranged at Morella. Fifty days spent in argument failed to induce Benedict to resign his position. Ferdinand was convinced that no other remedy was possible, and withdrew his support from Benedict, who then retired to the seaside settlement of Peńíscola, where he proceeded to issue a series of arguments showing that he was the only genuine Pope, and that it was impossible to dispute the legitimacy of his election. A second meeting at Perpignan, at which the Emperor Sigismund was present and did his best to persuade Benedict to resign, proved equally fruitless. Ferdinand proclaimed that he should be disregarded, and that none of his subjects should refer to Benedict, or Pedro de Luna as Ferdinand styled him, in ecclesiastical matters, but should refer these to the General Council. This example was followed by the other rulers in the Spanish peninsula, and, whatever may be thought of Ferdinand's action, it cannot be denied that no other policy seemed possible if the unity of the Church was to be restored.

Differences also arose between the King and his subjects upon financial matters. The royal incomes had been considerably diminished by the negligence of earlier rulers, [210] and the unwillingness of subjects to contribute. Ferdinand was a prince of liberal views, who was anxious to give petitioners even more than they asked. It is also probable that his administrative experience in Castile had accustomed him to a greater freedom of action than he could hope to exercise when dealing with the Cortes of Aragon or Catalonia. Especially was this restriction obvious in the financial sphere, and the necessity of bargaining for concessions from his subjects was continually irksome to him. His view was that his predecessors had been forced to barter the rights of the Crown in order to gain the necessary supplies for carrying on the Crown business, and he proposed to restore the Crown to its former position and so to avoid the necessity of continually harassing his subjects with small demands. His conflict with the municipality of Barcelona will show the kind of difficulty which he had to encounter and the character of the opposition with which he had to deal. On returning to Barcelona, after concluding his negotiations with Benedict, it became necessary to supply the royal household with meat and other provisions, and it appeared that the purchases, even when made by the King, were subject to a tax from which the clergy and the nobility were free. This the King refused to pay. An uproar followed. It was asserted that he was infringing the ancient rights of the town. The Council of the Hundred was called together and the King summoned the President, one Juan Fivaller, to an interview. He pointed out the injustice of demanding a tribute from the King which was not required of the most inferior clergy, and, when he was reminded of his oath to observe the ancient customs of the town, he replied that that oath obliged him no less to maintain the ancient rights of the throne, and in particular the royal revenues. Fivaller then urged him not to attack the Catalans upon a question of privilege, however small, which might be regarded as a breach of the convention between the King and themselves. Ferdinand paid the amount required, and left Barcelona the next day, declining any further communications with the inhabitants, who sent messengers after him begging him not to leave their country, and asserting their readiness to render him any services in their power. This combination of intense attachment to every article specified in the ancient privileges of their town, [211] the proposal to abrogate any of which aroused universal resentment, together with the apparently inconsistent protestation of loyalty to the King and desire to profit commercially by the presence of his court, is characteristic of the people with whom Ferdinand had to deal, and was no doubt intensely exasperating to any ruler of absolutist tendencies.

Ferdinand went as far as Igualada, about a day's journey from Barcelona, where his health was so impaired that he could travel no further, and in April 1416, he died after a reign of only four years, at the age of thirty-seven, according to the majority of the annalists. He had barely had time to compose the disturbances which the interregnum had brought about or to learn the peculiar character of the people with whom he had to deal, and to this fact no doubt are due the adverse opinions upon his character which have been passed by some historians. None the less, his death was a misfortune to the country. The titles of "El Justo" and "El Honesto" which have been given to him, were not undeserved. His personal life was blameless, and he left behind him none of the illegitimate progeny so often attached to the names of his predecessors. Simple in his habits and an indefatigable worker, he seems to have been endowed with that gift of sympathy which enabled him to estimate the grievances and the characters of contending parties. There is no evidence to support the suggestion that his abandonment of Benedict XIII was an act of bad faith towards one who had secured his election to the throne nor that he had bribed any of the other electors for the same purpose. On the contrary, his efforts to secure the unity of the Church can only be regarded as laudable, even if they were based upon a misconception of the future powers of the papacy in Europe, upon which subject his contemporaries were no more enlightened than himself.

Note for Chapter 14

See genealogical chart.

This work was originally published by Methuan Publishing Ltd. in 1933.

Pagination of the original edition is indicated set off in brackets, as in [19].

Ample your information on Aragon

If you want to extend your information on Aragon you can begin crossing another interesting route is the Mudejar, Patrimony of the Humanity, also you can extend your cultural knowledge on Aragon examining its municipal and institutional heraldry without forgetting, of course, some of its emblematics figures as Saint George Pattern of Aragon also book of Aragon.

Also Aragon enjoys a diverse and varied Nature where passing by plants, animals or landscapes we can arrive at a fantastic bestiario that lives in its monuments.

The information will not be complete without a stroll by its three provinces: Zaragoza, Teruel and Huesca and his shines, with shutdown in some of its spectacular landscapes like Ordesa, the Moncayo or by opposition the Ebro.

Also you can dedicarte to the intangible ones: from the legend compilation that also does to universal Aragon you can persecute the presence of del Santo Grial in Aragon.